Multiculturalism may be a fashionable neologism of our times, but as a cultural fact of American life it is considerably older than the Constitution. Even worries about its danger to national unity are hardly new. As early as the 1750s, Benjamin Franklin complained about the Germans' flooding into Pennsylvania: "Why should the Palatinate boors be suffered to swarm into our settlements, and, by herding together, establish their language and manners, to the exclusion of ours?" he asked in 1751. Their large number caused Franklin to wonder why "Pennsylvania, founded by the English," should "become a colony of aliens who will shortly be so numerous as to germanize us, instead of our anglifying them?"

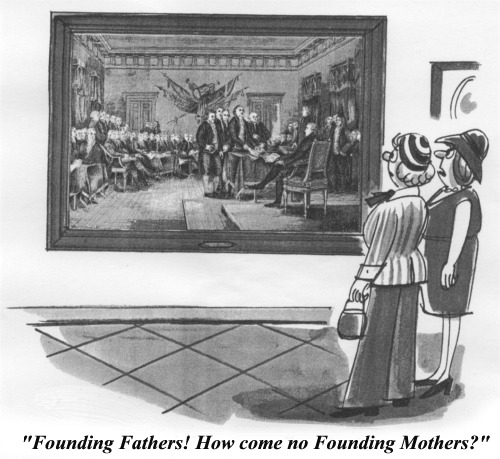

Indeed, the diversity of Americans was sufficient at

the establishment of the country to impel the founders*) to break decisively with

an age-old European tradition and deliberately sever in their new Constitution

any connection between church and state. America was simply too varied in

religions to have a national church - a decision whose cultural and political

significance becomes clear when comparing the United States and Europe, a region

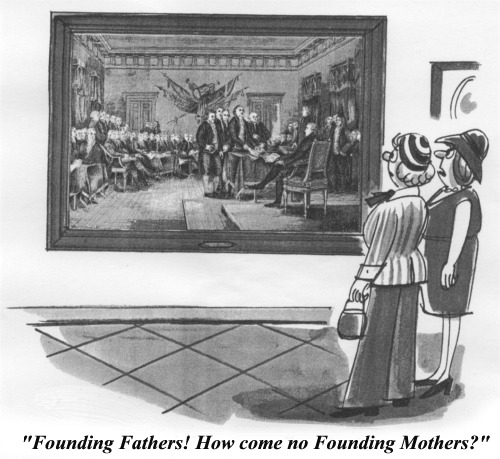

in which religious strife**) has served as an enduring source of internal division

and conflict.

But if Americans could not be identified by a common or state-supported religion,

it was not at all clear that the Union of disparate states created in 1787 was

to be anything more than an "experiment". America, a nation both

diverse and free, without a standing army or a history of unity, needed some

source of national identity.

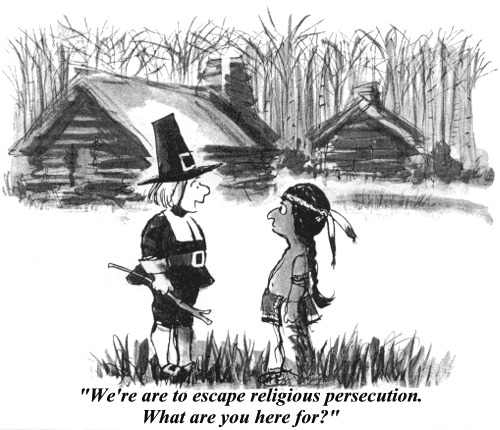

When the Civil War ended for good that aspect of the search for nationhood, it also established the principle of equality along with freedom as the heart of the American political and social polity. Both ideas, to be sure, had been implicit in the Revolution's declaration of independence from Britain, but only with the Civil War and the Reconstruction of the South which followed (1866 - 1877) was inclusion and equality explicitly applied to a racial group, in that case, the recently emancipated slaves of African descent ***) - though Lincoln, it's worth recalling, had doubts that blacks could he integrated into American society.

Behind that enunciation of inclusion and equality stood the assumption that in time the principle would erase or largely eliminate the differences in demeanor, style, and history between new and established Americans.

(From C.N. Degler, "A Challenge for Multiculturalism" in New Perspectives Quarterly, 1991) (Die Ouellenangabe ist nicht zu übersetzen)

*)CARTOON #1: Founding Fathers

**)CARTOON #2: religious srife

***)CARTOON #3: “inclusion and equality ...”

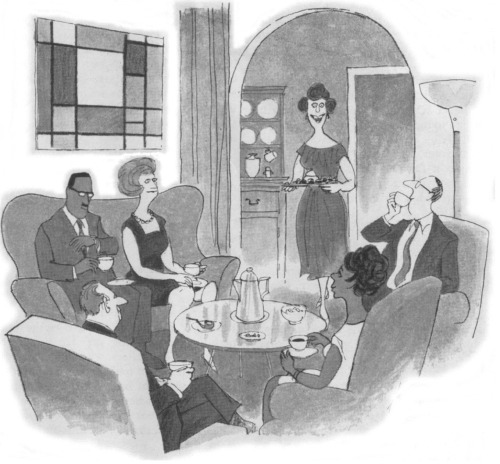

“Heavens,

don’t worry about trains!

Marie and Jeff can drop you off in

the ghetto

on their way back to Westchester.*)”

*)Westchester

County, N.Y., just north of the Bronx

back to Texterschließung WS 2005/2006, index back to homepage

THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE