back to Texterschließung WS 2005/2006, index back to homepage

THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BHOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE

WS 2005/2006 Preuß Texterschließung Staatsexamen Frühjahr 1981: Text 6

The

Orwellian world is one that could have a strong initial appeal to the young. It

has a striking anarchic feature - a complete absence of laws. It treats the past

as a void to be filled with whatever myths the present cares to contrive. It

sets up, as a group to be despised, a vast body outside the pale, devoted to

past traditions, reactionary and conservative, essentially old. Oldspeak*

is rejected as having no power to express that eternal present which is

youth's province as well as the Party's; Newspeak* has the laconic

thrust of the tongue of youth. The programme, if not the eventual reality, would

find its most energetic supporters initially among the young, all happily ready

to destroy the past because it is the past, and to accept the Ingsoc* revolution

as it has already accepted the mixed mythology of Mao, Che Guevara, Castro and

Bakunin himself. It is the prospect of revolution that counts, with its

connotation of the liquidation of the outdated and the glory of the fresh start.

What comes after the revolution is another matter.

If,

on the other hand, the new strikes even the innocent and ignorant young as

somehow suspect, it can only be scrutinized in the light of standards derived

from the past. I mean, of course, those sifted nuggets that add up to what we

vaguely call a tradition, meaning a view of humanity that extols values other

than those of pure bestial subsistence. The view is, alas, theocentric and rests

on an assumption that cannot be proved - namely, that God made man to cherish as

the most valuable of his creatures, being the most like himself. It is not the

aggregate of humanity that approaches the divine condition but the individual

human being. God is one and single and separate, and so is a man or a woman. God

is free, and so is man, but man's freedom only begins to operate when he

understands the nature of the gift.

Human

freedom is the hoariest of all topics for debate: it still animates student

gatherings, though it is often discussed without definition, theological

knowledge or metaphysical insight. Augustine and Pelagius confront each other on

the issue of whether man is or is not free; Calvinists and Catholics shout each

other down; even in Milton's hell the diabolic princes debate free will and

predestination. The pundits of predestination affirm that, since God is

omniscient, he knows everything that a man can ever do, that a man's every

future act has already been determined for him, and therefore he cannot be free.

The opposition gets over this problem by stating that God validates the gift of

free will by deliberately refusing to foresee the future. When a man performs an

act that God has refused to foresee, God switches on the memory of his

foreknowledge. God, in other words, is omniscient by definition, but he will not

take advantage of his omniscience.

*Die unterstrichenen Wörter werden unübersetzt übernommen. from: Anthony Burgess, 1985, London 1980

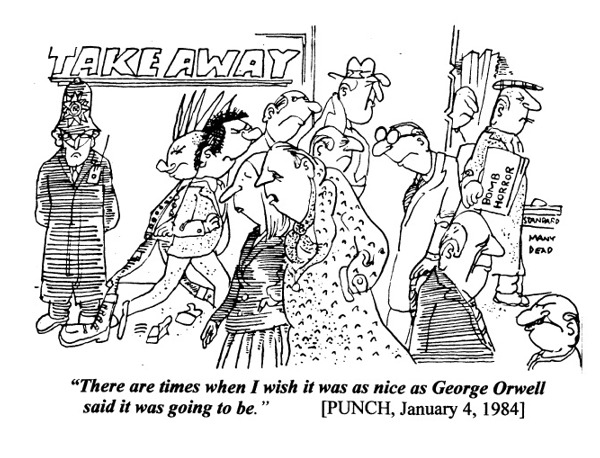

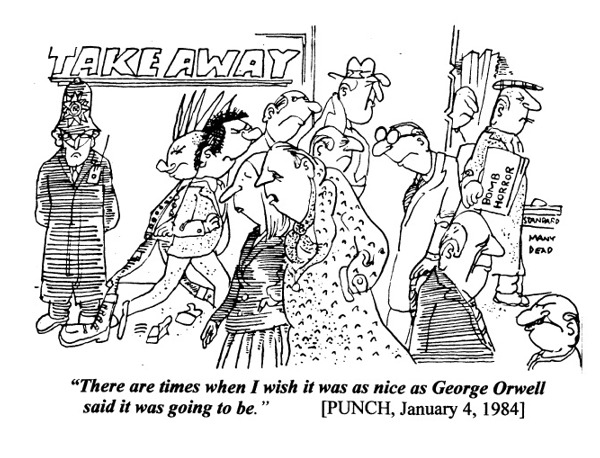

ORWELL

THAT ENDS WELL

back to

Texterschließung

WS 2005/2006, index

back to

homepage

THE

BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BHOTTOM LINE THE

BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE