back to Texterschlie▀ung WS 2005/2006, index back to homepage

WS 2005/2006 Preu▀ Texterschlie▀ung Staatsexamen Herbst 1980: Text 4

If the United States were really a melting-pot, we should expect our

people, coming as they do from all races, to represent as it were the sum

total of what all races might contribute to the common wealth of humanity. We

might expect, therefore, to find in the United States much art, fine science,

and a noble poetry. That has indeed been the expectation of optimistic Americans,

and the expectation has furnished the text for much comment from critical

foreigners, who upon visiting our shores have marveled, perhaps with an inward

satisfaction after all, that a country so new and supposedly full of energy

should have as yet disclosed so meager an utterance in things of the spirit. The

fact is, however, that a nation which has dropped its past has thereby dropped

the instruments of expression. Language is but a series of sounds, mere groans

and noises if you choose, until the ear has grown accustomed after many

centuries to detect the significant shades and intonations of the specific groan.

No language can be improvised, if the audience is to understand the speaker. The

larger fabric of language, the racial memories to which an old country can

always appeal, obviously do not exist in a land where every man is busy

forgetting his past, separating himself from the memory of what his forefathers

felt and said. Without tradition there can be no taste, and what is worse, there

can be little for taste to act upon. We have indeed some approaches, some faint

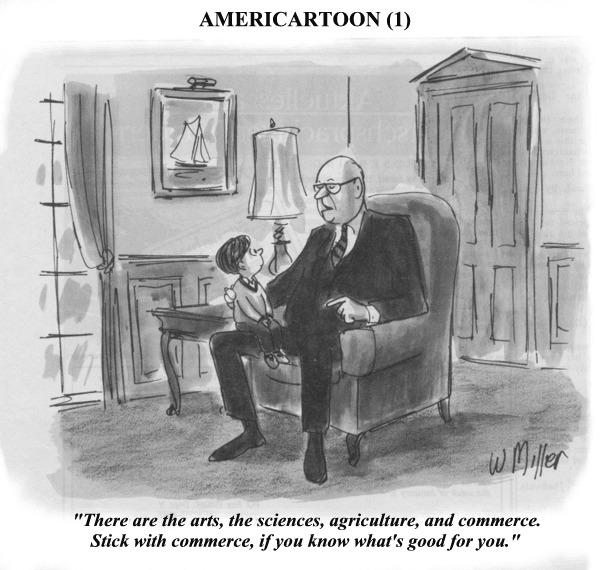

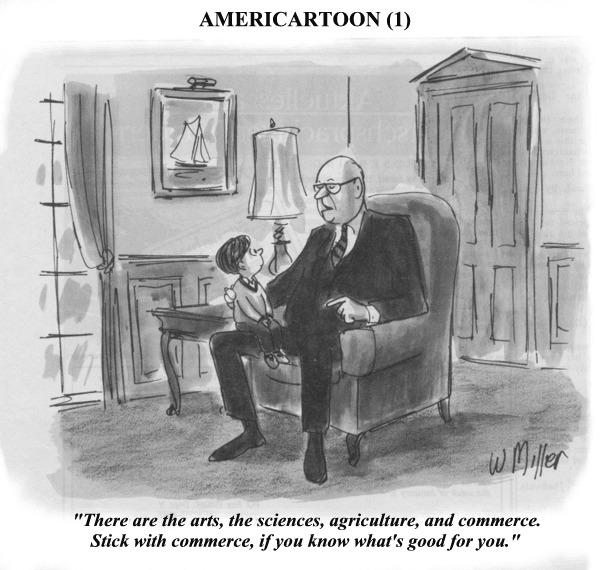

hints and suggestions of a national poetry. The cartoon figure of Uncle

Sam, for

example, a great poet could perhaps push over into the world of art, but unless

the poet soon arrives there will be few Americans left who can recognize in that

gaunt figure the first Yankee, the keen, witty, audacious, and slightly

melancholy type of our countrymen as they first emerged in world history.

If our lack of a past handicaps us in the matter of art, it handicaps us also in

manners, since manners are themselves an art. Those societies which have a

traditional behavior have manners; other societies must improvise their behavior

as they go along. If the American seems impromptu in his ways, it is really

remarkable that he does not seem even more so, since outside of the individual

home or the particular part of the given city in which he may reside he is

subject to no formulas of behavior, and if he has manners he is likely to

suggest to his countrymen that he is imitating the foreigner. You may talk or

walk or may conduct a drawing-room conversation in an English way, in a French

way, in an Italian way, or in a German way; but it would be

a bold critic who, after knowing America, would say just what is the

American way of doing these things, since Americans on the whole do those and

other things each as he pleases. There may seem at first sight little reason to

object to a spontaneity of manner which has managed to slough off much impedimenta and

to have brought to the fore instinctive friendliness and unveiled sincerity. But

there are other uses of behavior than merely to seem amiable; manners become at

times vitally significant as language, and it is difficult indeed to speak with

manners as with any other form of discourse unless the hearer is conversant with

the particular tongue.

From: John Erskine, American Character, New York 1920

back to Texterschlie▀ung

WS 2005/2006, index

back to homepage

THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BHOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE