Perhaps we grow coddled, too well guided in too much

fiction. Editors can be very helpful, but perhaps sometimes too determined that

no reader shall ever lose their way. In this bright new postmodernist and

deconstructionist world, something seems to me in danger of being lost: an

obstinate individualism, almost a bloody-mindedness. The reek of the ego, if you

are a cynic, though I'd prefer to call it a secret conviction - harder than ever

to hold in this overpopulated world - of one's own uniqueness. A suspicion that

individual language, the personal use of it, can't always be reduced to a

rehashing of someone else's old mutton, that it's good that some people do «see»

nature and history (human destiny) differently; and also that the secret way

through the shamanistic magic of creating narrative is some how always single.

Ulverton, thank the gods, helps support my point. It is the most interesting first novel I have read these last years. Outwardly the story of a Wessex downland village, it is told in a dozen very varied accounts (starting in Cromwellian England and ending in the 1980s). What I found remarkable in this long fictional sequence of episodes from our rural and agricultural past was their skill and vividness. One frequent symbol, the wild clematis, is not introduced so often for nothing: Thorpe's characters and events constantly intertwine, snake their way through the generations. This interconnectedness is partly what gives the book its rich and dense texture; and it gives it its sense of crossing rhythms - the slowness of time and its ephemeral transience.

We aren't used to the many deep matters Thorpe evokes

or touches on, nor to such a thorough grasp of the complex nature of our

national rural past, and through it, of all existence itself. He lives in France

and some of that country's literary expertise in getting close to the

imaginative reality of the past haunts his work, with an added skill in

uncovering the endless English ways we have found to mask and conceal our

paradoxical nature. He seems equally at home with dialect, farming language and

(most importantly) the «sound» of period. He has truly great skill with

different tones of voice -perhaps the hardest thing for any novelist to acquire.

For this doesn't just require a vocal skill at mimicry, but the knack of

conveying it in print. The last episode in this novel is a mock script for a

documentary on the village. It is sour-funny, as a hideous Thatcherite developer

moves in and tries to ride rough-shod through the usual bureaucracy. Most of the

modern village express themselves in a language so tired and debased that it

explains in itself why England these days so often seems self-torpedoed. If you

are losing your language, you are in grave danger of losing yourself.

adapted from: John Fowles, Ulverton by Adam Thorpe, The Guardian, May 28, 1992

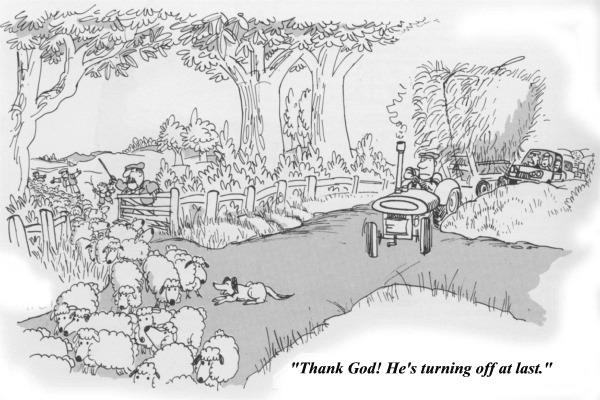

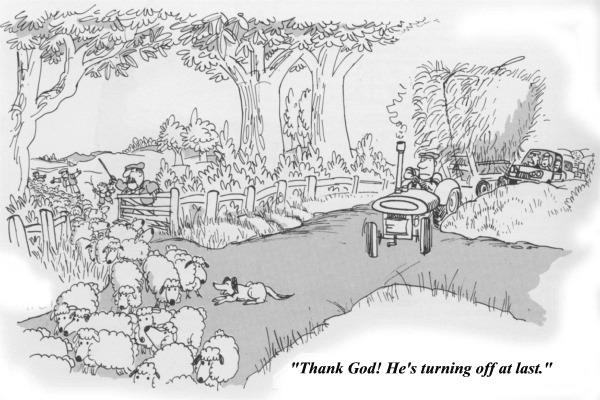

CARTOON: Life in the country

back to Texterschließung SS 2006, index model answer: AFTER Klausur!

THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE THE BOTTOM LINE